Tenant Farming

Non-indigenous settlement of Chilliwack began in the late 1850s and early 1860s. The first pre-emption granted in Chilliwack was to Jonathan Reece, who pre-empted land in current-day downtown Chilliwack in 1859. Most land that was provided to newcomers was granted as part of the Land Ordinance Act of 1860. The Act, passed by the Government of Canada, allowed re-settlers to occupy land at minimal cost to begin their farms on the conditions that they would increase the market value of the land and that they would not be absent from the land for more than two months of the year. Twenty four years later, the province of British Columbia passed the Act to Prevent Chinese From Acquiring Crown Lands, a discriminatory law which restricted Chinese immigrants from engaging in this practice.

Photo of workers on the Reuben Nowell farm with a steam-powered threshing machine, c. 1870-1880.

Chilliwack Museum and Archives, PP500480

The most common farm-based occupations for Chinese immigrants were tenant farming and labouring. Many farms, such as the Edenbank farm owned by Allen Casey (A.C.) Wells and the Evans’ farm owned by Allen Evans were active employers of Chinese labourers dating to pre-emption. Farm labourers had a variety of tasks, including clearing the land for agriculture, planting and tending to crops such as potatoes or hay and other farm chores. Chinese farm labourers worked on farms owned by their employers and were paid in exchange for their labour.

Seasonal work on farms could be found, particularly in the hops industry between 1900 and the 1920s. Chilliwack’s largest seasonal employer for a time, the hops industry employed hundreds of seasonal workers from Indigenous, Chinese, Japanese and South Asian Communities at hop yards such as the Hulbert Hop Company and British Columbia Hop Company.

Abacus used for counting by Chinese workers at the British Columbia Hop Company in Sardis.

Chilliwack Museum and Archives, 1990.028.001

While permanent work existed in the hops industry, positions were rare and most responsibilities in the hops fields, such as picking or pruning, were temporary and subject to crop yield. The number of Chinese workers in Chilliwack’s hops fields decreased sharply in the 1920s and 1930s, reflecting a discriminatory shift in hiring practices favouring the growing Mennonite community and a preference for Caucasian workers during the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Sing and co-worker spraying hops at the Hulbert Hops Gardens, c. 1901-1937.

Chilliwack Museum and Archives, 1987.013.004

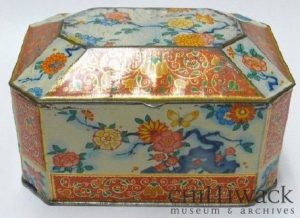

A gift from a labourer to their employer at the Evans’ farm.

Chilliwack Museum and Archives, 1979.031.001

Social relations between farm labourers and their employers were multi-faceted and workers often gave gifts to their employers as part of holiday celebrations. Listen to a 1983 interview between Penny Lett of the Chilliwack Museum and Historical Society and Doreen McCutcheon, where they discuss the life of Jim Lee, a Chinese farmhand from Chinatown South employed on Doreen’s family farm.

Chinese tenant farming was also popular in Chilliwack. Tenant farming is the practice of renting land to another person to farm in exchange for payment, usually in the form of cash or a percentage of produce grown on the land. In Chilliwack, the tenant farming system dates to roughly the 1860s and was key to transforming acres into arable farm land. Land for tenant farming was leased from property and farm owners.

Watch the video interview with Dr. Chad Reimer, author of Chilliwack’s Chinatowns, to learn more about tenant farming in Chilliwack.

View this video with a transcript.

Tenant farming provided advantages over other employment available at the time. While agreements reached with property owners traditionally involved stipulations such as the removal of brush and trees from the parcel of land rented, tenant farming provided a degree of independence to Chinese tenant farmers and had the potential to be lucrative enough to allow tenant farmers to save to purchase land, although those capable were the exception. Tenant farming grew immensely in popularity: in 1911, there were 49 independent Chinese farmers in Chilliwack, a 2,350% increase over the number of reported tenant farmers in 1901.

A 1922 Commission led by provincial Agricultural Minister Edward Dodsley (E.D.) Barrow as part of the drainage of Sumas Lake noted that Chinese farmers:

- Produced 90% of B.C.’s “truck produce”

- Produced 55% of the potato crop for the province

- Owned 5,000 acres of land

- Leased 10,030 acres of land

These are significant figures within the agricultural industry of British Columbia.