Colonization, Clearing and Settlement

Apart from the difficulties getting to the island, the fear of attacks by the Iroquois on the first Laval settlement complicated attempts to settle the island until the Great Peace of Montreal in 1701.

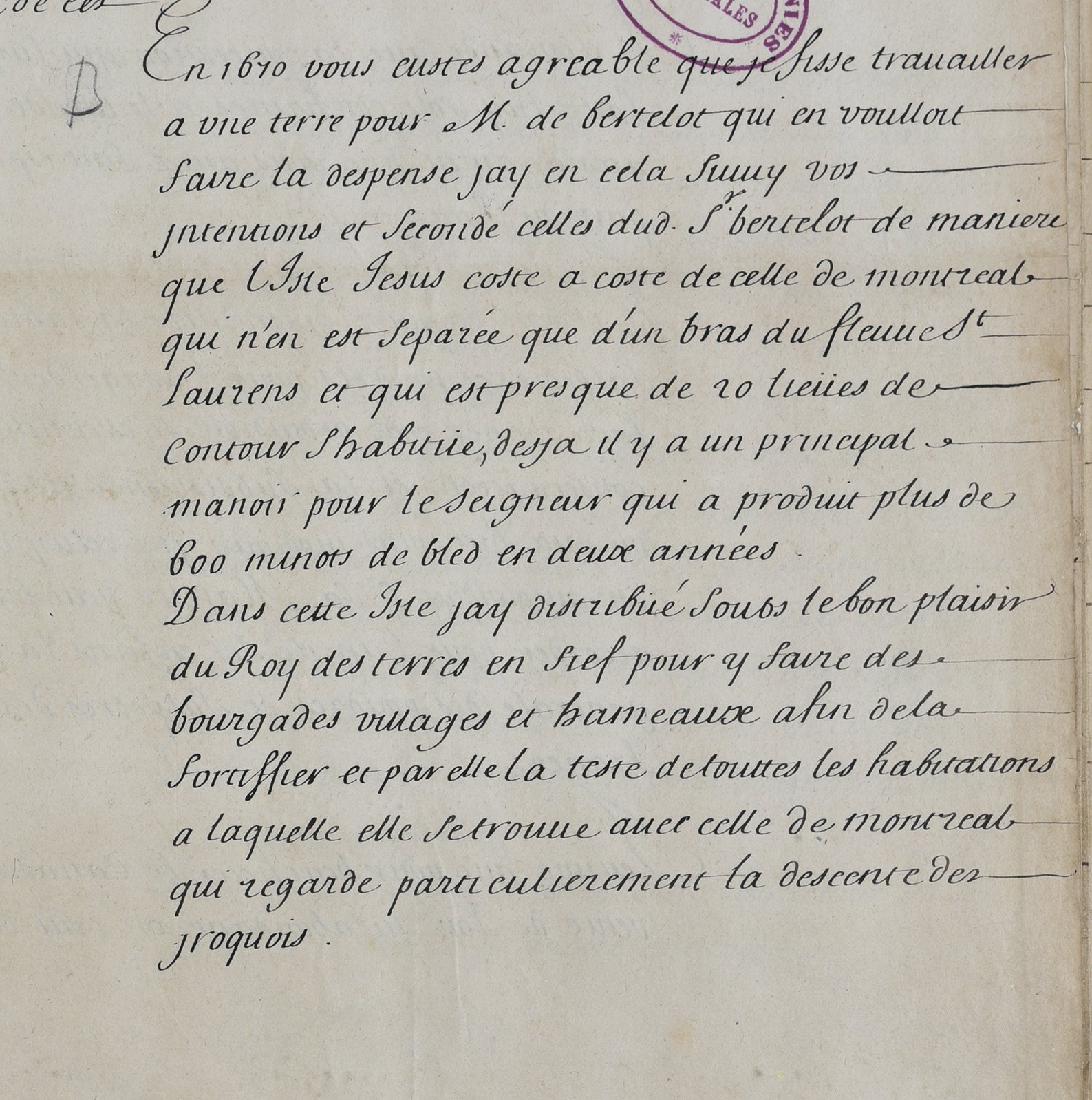

In 1670, Jean Talon, then intendant of New France, was tasked with preparing an inhabitable area on behalf of François Berthelot, adviser to the king of France. Talon undertook to develop the seigneurial territory, despite potential conflicts with the First Nations, by granting land to the colonists and building a manor, a fort, a mill and a sawmill.

This was the beginning of a subsistence economy. Extensive logging and early farming led to a local economic boom. Between 1670 and 1673, nearly 600 bushels of wheat were produced and a number of dwellings were built along the island’s shores.

The resulting calm following the signature of the Great Peace of Montreal between the French and the Indigenous peoples in 1701 led to an increase in the number of merchants and farmers on the island. This had a positive impact on the amount of trade between them. Some cleared a neighbour’s land for money, while others sold the wood and the crops that could be grown once the land had been cleared.

Thanks to the efforts of Talon and the seigneurs on the island, the population rose from 24 colonists in 1681 to 2,379 in 1765. The arrival and settlement of the Charbonneau, Labelle, Bisson and Éthier families at the end of the 17th century made an enormous contribution to the region’s economy.