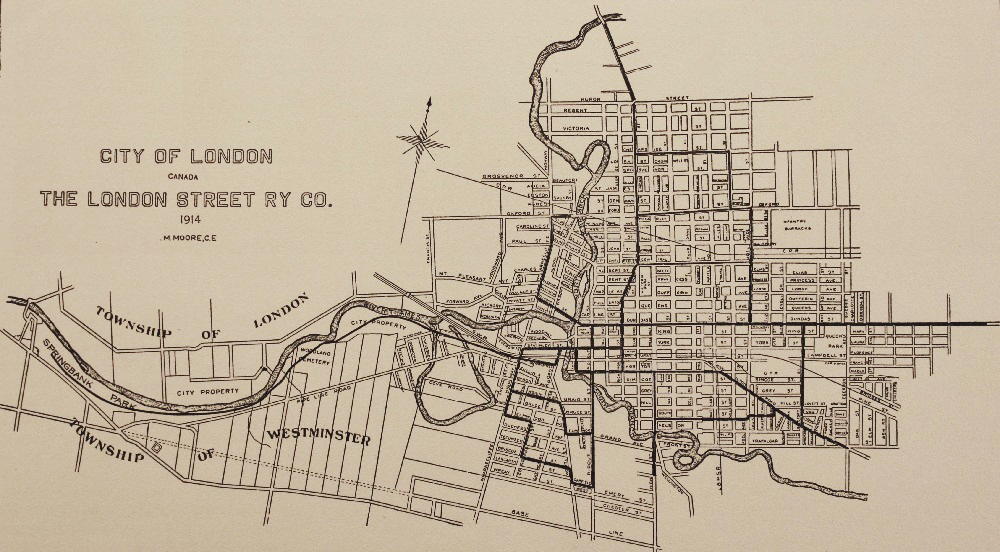

London, ON, in 1914

Streetcar Lines and City Boundaries

1914. Gardner, H.W., ed. London, ON, London Free Press.

“London Paying More for Butter than Montreal”

“Mayor Graham Wins Fight for People Against Street Railway”

“Manufacturers Athletic Association Plans Big Annual Field Day”

These are a few of the headlines that Londoners read in The London Evening Free Press throughout 1914. The newspaper had a circulation of 40,000 in Southwestern Ontario and many subscribers lived in London, ON.

It was a growing city of 55,000 and, after several annexations, development stretched to the boundaries of Wreay, Victoria, and Egerton Streets and Wharncliffe Road. Street name signs had just been installed in 1910. The wide, shady streets featured houses ranging from mansions to working-class cottages or crowded rentals. The inhabitants were largely of British origin, but there were also immigrants like Italians and Russians.

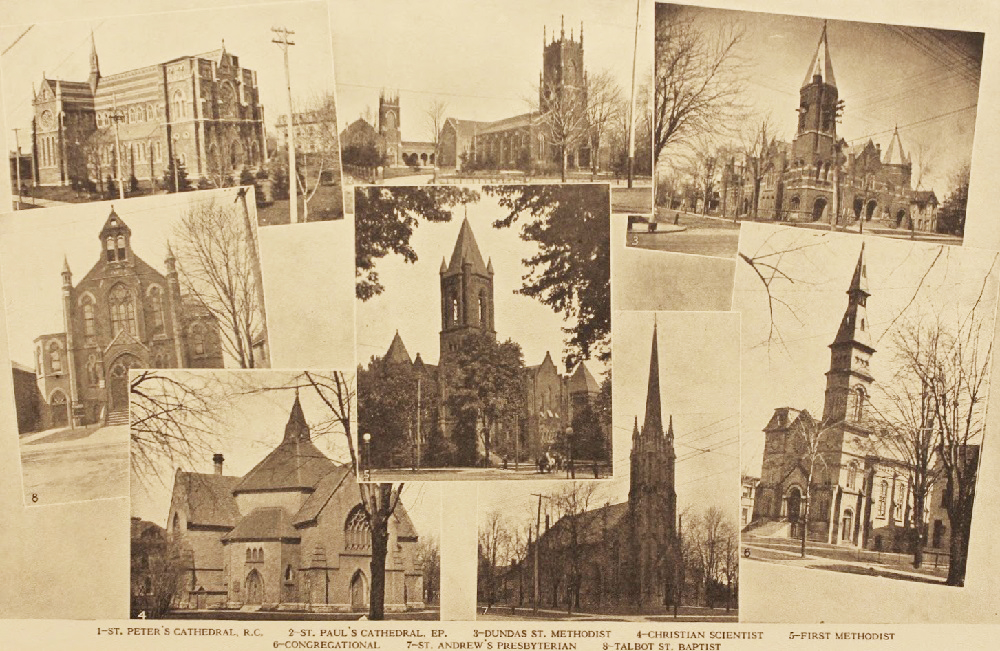

Londoners elected merchant Charles Graham as mayor for the third time in 1914, and he steered the city towards economic recovery from the previous year’s recession. Sir Adam Beck, long active in local politics, represented the city in provincial parliament, where he led the initiative to bring hydro-electric power to Ontario in 1910. Electricity was now cheaper and more accessible to Londoners. Other significant changes included the introduction of regular garbage collection in 1913 and the parcel-post system in 1914. Residents had access to many other public services and institutions. The original Victoria General Hospital and St. Joseph’s Hospital provided healthcare, as did a tuberculosis sanatorium, an asylum, and a convalescent home. For spiritual care, Londoners could choose among sixty churches, Anglican, Catholic, Protestant, etc.

Schools were also plentiful, including St. George’s Public School and London Collegiate Institute. Huron College and Western University offered higher level education. Western University was founded in 1878 in affiliation with the Anglican Diocese. When it became a city-funded secular institution in 1908, the university taught three disciplines: arts, divinity, and medicine. The institution underwent important changes in 1914. It appointed Dr. Edward Braithwaite as its first full-time president and Hilda Baynes as its first female faculty member. The university also changed its colours from purple and black to purple, red, and gold.

Students Exercising at Alexandra School

1914. Gardner, H.W., ed. London, ON, London Free Press.

The university gave London an element of sophistication, but at its heart the city was a major industrial centre, being, amongst others, the second-biggest cigar producer in Canada. More than 200 factories made everything, from candies to clothing, to calendars, to cars. Kellogg’s cereal and Labatt’s beer were well-known products across the province. Men, women, and children worked 45-60 hours a week for agencies such as the McClary and McCormick manufacturing companies. Financial firms like London Life Insurance Co. and the Huron and Erie Loan and Savings Co. were influential businesses.

Industries relied on London’s extensive railway network, which included transcontinental and American lines. More trains came into the city than any other in Canada. London also ran a streetcar system, which began transitioning to electric service in 1913. Sunday service was finally provided in 1914 and Londoners used it to go to church.

Churches in London, ON

1914. Postcard. Gardner, H.W., ed. London, ON, London Free Press.

Covent Garden Market

Ca. 1912. Photograph. ML, gift B.S. Scott 1959.042.020.

While religion was an important part of life, attendance was also boosted because members of sports leagues were required to attend Sunday School or church. People who preferred reading over running, could choose from 35,000 volumes at the London Public Library, expanding with a second branch in 1914. Other popular activities included cards, theatre, bowling, and billiards, while rowdier citizens gathered at King St.’s notorious “Whisky Row” hotels and bars. Across the street was Covent Garden Market, a centre of commerce still active.

Londoners joined many associations like the Humane Society, the Young Men’s Christian Association, and the Young Hebrews’ Social Club. Women had their own organisations, such as the Red Cross and the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire. They advocated for causes ranging from homelessness to musical education.

Springbank Park

1914. Postcard. LRPL

In the early 1900s, there were three main parks in London: Springbank, Queen’s, and Victoria. Springbank Park was the largest natural park in Eastern Canada, and Londoners could take moonlit trolleys rides there. In 1914, an amusement park opened just beside it. The parks hosted picnics, tennis, baseball, ice skating, and many other activities. Queen’s Park, in the east end of the city, began holding the ever-popular Western Fair in 1887. In 1912, the Governor-General unveiled Victoria Park’s Boer War (1899-1901) Memorial amid great fanfare.