1

Mary Teresio from Two Hills, Alberta tells the story about arriving in Canada and settlement in a new country.2

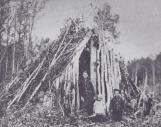

The first shelter of a Ukrainian pioneer family was called a boorday or kurnik1891-1914

Manitoba, Canada

Credits:

Credits:National Archives of Canada

3

My maiden name was Mary Drabaniuk. My parents were poor peasants. I was born in the village of Vovchivtsi, Sniatyn District, Slanislav Province. The village is situated on a hilltop. Our house was in the charming valley below, close to a flour mill, between the rivers Chorniava and Prut.I remember that our house was always full of people, especially in winter, who were waiting for their turn to grind their grain at the nearby mill. There wasn't enough room inside the mill where the people could take shelter, so they waited in neighbouring houses. On many occasions I listened to tales telling of evil spirits and witches as the waiting people talked while away the time. But mostly I heard complaints about the shortage of household necessities, about there not being enough bread to eat, and about the government predators who came and pulled the sheepskin coats from the backs of their victims for taxes.

Our parents had to work for wealthy farmers and had us small children look after a dozen ducklings and a couple of piglets at home. We did this as we best knew how. One day, when we were thus alone, we noticed that a tax collector was coming down the hill towards our house. Thinking that he was coming to collect the tax, I, who was eight years old, together with my sisters, caught the piglets and hid them under the bed. The ducklings we covered with a blanket in one corner of the room. I myself hid under the bed but my feet were still showing. The collector looked in through the window and then went away, leaving us in peace. It was something like the anecdote by Stepan Rudansky where mother has gone to town, but has left her feet behind under the bed.

Our father was a cheerful good-natured person and we always liked to be with him. He was very fond of children and we were never bored when he was at home. When I was eight years old he sold the land, leaving only the house, and went to Canada. My mother and the four children stayed behind. My older sister, Frosina, who was thirteen years old, was already working in the landowner's beet field. She often complained about having to get up so early in the morning and about having to work so hard from sunrise until sunset, with only a piece of bread and a small onion for lunch. In winter, my mother and my older sister spun flaxen yarn out of which they made cloth for the richer peasants. I was only permitted to work with the coarse hempen yarn.

I wanted very much to grow up so as to be independent like my sister who already was earning twenty kreutzers a day! It didn't take me long to learn to do cross-stitch. I did embroidery mainly for other girls and not much for myself, because I was only given coarse cloth to work with, on which I didn't want to embroider.

We lived in poverty for five years after my father had gone to Canada. Finally, we convinced our mother that we should all go to Canada. Our father sent us some money and our mother sold all that there was of any value. With this we were able to pay for our passage. We prepared to leave at once as soon as the documents came from Lviv. We counted our money over and over again to make sure that we had enough to get us to Quebec City or Montreal. Our tickets included passage all the way to Pincher Creek (Brocket), Alberta, where my father was working as a section hand for the Canadian Pacific Railway.

When we arrived in Lviv, an agent called my mother into his office so that she could pay for the steamship tickets. We three children (our eldest sister, Frosina, remained behind in the old country) stayed in the waiting room. Seeing that my mother couldn't read, the agent used his cunning to get as much money from her as he could, leaving her with only fourteen Rynskis for the remainder of the journey.

My mother came back to the waiting room in tears after her interview with the agent. "Whatever are we going to do when we get to Canada?" she lamented. "Nor do we have anything to go back to in the village."

I tried to cheer my mother up as best I knew how: "Mother, we have the steamship ticket to Montreal or Quebec City and the fare is paid to our destination in Alberta. We'll get to father somehow, even if we have to eat less along the way."

But the incident in Lviv wasn't the last of our troubles. We arrived in Antwerp in Belgium where we had to wait six days for a ship. Apparently, the dishonest agent in Lviv hadn't paid for our accommodations and meals as he was supposed to have done. My poor mother was very upset and worried. Fortunately, some kind people among the other immigrants collected enough money among themselves to pay for our six-day stay in Antwerp.

When we got to Canada we were supposed to have twenty-five dollars to show to the immigration authorities, but all we actually had left was twenty-five cents! My mother became sick as a result of all this, but I wasn't able to help in any way.

There was a young woman with her small son who had shared the same cabin aboard ship with us. Seeing how desperate my mother was, she said to her: "Don't cry. When we come before the immigration authorities I'll lend you twenty-five dollars, which you can give back to me as soon as we pass through the inspection." But things didn't work out that way. My mother and the young woman became separated in the milling crowd, so we ended up before the authorities with only twenty-five cents. The inspectors talked among themselves and then gave my mother a blue card and told her to go outside. We thought that now we would be able to continue on our journey to Alberta without further hindrance, but when I handed our papers to the conductor, he pointed to a large building, the one from which we had just come. Now we were afraid that they wanted to send us back to the old country.

A man who had noticed our predicament came up and asked us to show him our papers. He took the blue card that had been given us and went to the large building. Soon after, he came back with some bread, Polish sausage, apples, oranges and biscuits. Then he took us to the train with the food that he had just bought.

At last, after several days on the train, we arrived in Brocket, Alberta, where we were met by my father. He was a section man on the railroad. He didn't earn very much. Some friends of his advised him to go to work in the mine in Michel, British Columbia, where the pay was better.

What awaited us in Michel was a large single-roomed shack in which there were three beds and a stove. The five of us and three workers who had come from our village shared these quarters. My mother cooked for all of us. We lived rent-free in this shack in exchange for my mother's cooking.

Although the pay was somewhat better in the mine than it was on the railroad, the miners spent their earnings faster because there was a lot of heavy drinking going on. As soon as the miners came out of the mine on Saturday night, they would get two barrels of beer and roll them home, and bring a few bottles of whiskey to boot. The drinking went on until it was time to go down into the mine on Monday morning.

Even today I find it hard to imagine how our family managed to stand it during that first winter with all the drinking that was going on every weekend. My mother convinced my father to send her and the children to live at her brother's place on the farm in Slava, Alberta.

We came to my uncle's place in Slava in 1911. Here we also lived in a single-roomed shack which was shared by my uncle and aunt and their two children. It was summer and we were happier there. We spread some fresh hay in a shed where we slept, enjoying the fresh air. My uncle had two cows so we had fresh milk and cottage cheese. We no longer had to go hungry.

My uncle advised us to plant some potatoes for our own use during the winter. Later, my mother came across an abandoned house and we took possession of it. It had belonged to a man who had gone back to the old country. Unfortunately, the house was infested with bedbugs. We planed down the rough log walls and plastered them over with fresh mud. Later we whitewashed the walls and floor with slaked lime. We went into the bush and cut some saplings out of which we fashioned beds. My father sent us some money with which we bought a tin box-stove heater. We also did our cooking on this box-stove. And so we began our second winter in Canada.

There was a lot of bush on the farm. With our help, my mother cut firewood for the stove and we carried it to the house.

There was still an unclaimed homestead not far away from where we were staying. My uncle in his kindness drove to Vermilion some thirty-five miles away and bought this homestead in our name. When my father came home from the place where he had been working, we bought a cow and began farming in earnest. With the help of some neighbours, my father built a two-roomed house where we moved the following spring.

I will never forget the day that we moved to our farm. My father borrowed a pair of oxen and a hayrack on which we loaded our household belongings and set out on the four-mile trek to the farm. One of the oxen was large and the other small; one pulled to the left and the other to the right. On the way, they became obstinate and pulled the wagon off the road into a slough. It took a long time to coax the oxen back onto the road again.

We worked very hard on our homestead, as did other poor farmers on theirs. My father and mother cut down the trees, while the children gathered the branches and underbrush into piles which we burned. How happy we all were when we sowed our first wheat on the ten acres that we had cleared. We also grew some vegetables. We no longer had to worry about going hungry.

As yet, there was no school in Slava, so the children had to stay at home. People didn't have the money to send their children to study in town.

Peter Teresio and I got married in 1914. We settled on a homestead in Lanuke. We took my younger sisters with us and they started attending school.

My husband enjoyed reading ever since he was a boy. He subscribed to several newspapers: Vpered (Forward), Zemlia i volia (Land and Freesom), Robochy narod, and the magazines Dobra novyna (Good News) and Literaturno-naukovyi visnyk (The Literary-Educational Herald). He also read the Polish paper Rolnik (Agriculturer).

In 1914, we organized in Lanuke an educational Association named after Mykhailo Pawlyk and built our first Ukrainian Farmers' Temple.

It would be nice to list the names of all of the founders of the Mykhailo Pawlyk reading hall, but I will only mention several of them, namely, Andrew Buk and Nicholas Khrapko in Vancouver, William Humen in Lanuke and Peter Teresio in Two Hills.

Our association later linked up with the Ukrainian Labour-Farmer Temple Association. We studied and carried on with our cultural work as best we knew how. We presented plays on stage under Nicholas Khrapko's direction. Later, our director was Nicholas Nykyforuk who is now living in Edmonton. He organized a mandolin orchestra with which we went on tours in neighbouring districts. Some of the younger people still mention these concerts.

We also had a choir. We organized a branch of the Women's Section of the Ukrainian Labour-Farmer Temple Association. We held educational evenings which were also attended by our children. We made every effort to teach our children to be upright, good people. We especially took a strong stand against drinking because drunkenness brings shame on both the individual and the community as a whole.

Both my husband and I have held responsible positions in the organization. I was recording secretary for many years and I used to do prompting during the performance of plays. I have also written some articles for our press, especially for the magazine Robitnytsia.

And now I have reached old age. I have many happy memories of our organizational work. And we continue to read the progressive press and are interested in cultural-educational and community activities.

MARY TERESIO

TWO HILLS, ALBERTA

interview by Peter Krawchuk

4

Sod roof on an early pioneer home1895

Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

Credits:

Credits:Ukrainian Historical Pioneer Village

Kobzar Publishing

Vasyl Pylypiuk