2

Canoe River Train Wreck21 November 1950

Canoe River, Valemount, British Columbia, Canada

Credits:

Credits:Korean Veteran Association Unit 21

3

The CrashAt 10:40 a.m. Tuesday morning on November 21, a westbound troop train and an eastbound Transcontinental train collided head on at Canoe River.

The Transcontinental was a Vancouver - Montreal passenger train carrying an unknown number of people. The troop train was carrying 23 officers and 315 other ranks of the Royal Canadian Horse Artillery. The men were all gunners making their way to Korea to aid South Korea in a battle. This troop train was one of several, coming from Fort Shilo, Manitoba, and heading to Fort Lewis, Washington. It was also one of the few that did not have a doctor aboard.

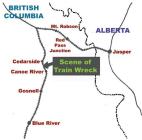

The troop train arrived at Red Pass at 9: 15 a.m. The conductor John Mainprize picked up Order No. 248, which gave the troop train clearance to Gosnell, where they were supposed to await trains No. 2 and 4. At Blue River, 78 miles south of Red Pass, Maurice W. Graham, conductor of train No. 2, the Transcontinental, picked up his copy of order No. 248 that advised him that the troop train would clear his train at Cedarside, and train No. 4 at Gosnell. Running on time, the Transcontinental left Blue River at 9:05 a.m.

At Jackman, 17 miles east of Canoe River, the troop train left the last section of track protected by an automatic block system, which might have alerted the engineers to the presence of both trains on the same track. Both trains thought that they had right of way.

Two loggers, Bill Tindill and Harry Patterson heard the whistle of the troop train and saw the Transcontinental coming. They waved frantically to try to warn the approaching trains, but the fireman of the Transcontinental thought it was a greeting and waved back. The two loggers could do nothing but watch in horror as the trains collided.

Damage to the Transcontinental and its passengers was minimal. It included a ruined engine, several cars going off the track, several bumped heads aboard the train, and the death of the engineer and fireman.

The fate of the troop train was much different. The engine of the troop train shot into the air and came down onto the second coach, crushing it onto the tracks. The first car telescoped and landed on top of the front section of the third coach. The steel cars were fine, but the old wooden cars were crushed. 21 people died from the troop train - 17 gunners, an engineer and a fireman. Afterwards an oil fire broke out in the wreckage, making retrieving and identifying bodies even more difficult.

4

Scene of the disaster21 November 1950

Canoe River, Valemount, British Columbia, Canada

Credits:

Credits:Korean Veteran Association Unit 21

5

Responding to a tragedy: Soldiers on the train remove injured men at the crash site21 November 1950

Canoe River, Valemount, British Columbia, Canada

Credits:

Credits:Korean Veteran Association Unit 21

6

After the CrashThere was no doctor on the troop train, and there was only one on the Transcontinental. The conductor of the Transcontinental train located 29-year-old Dr. P.J. Kimmit of Edson. When the troops saw a doctor coming, they were so happy, they chanted M.O. (Medical Officer). Mrs. Lennie of Edmonton and Mrs. Kimmit acted as nurses and Jack Cook, C.N.R. regional first aid officer, helped as well. They treated all soldiers as best they could, and retrieved the dead. They used one intact car as a morgue. With both engines gone, the train had no heat. When the crash occurred, the skies were cloudy and there was already about 6 inches of snow on the ground. Slightly after the crash it started snowing again. Because of the lack of heat, freezing temperatures soon became a problem. All soldiers acted with experience beyond their years, and helped the best they could.

The crash had brought down all communication lines, so there was no way of radioing for help. Luckily, Bill Fischer, a telegraph operator who was riding the northbound train, was able to rig up an emergency telephone to communicate with his divisional headquarters in Jasper. A hospital train arrived from Jasper within three hours. A relief train was sent from Kamloops. The Transcontinental was pulled back to Kamloops. The hospital train stopped at Jasper for several hours to have the ice cleaned off. It also stopped in Edson and Spruce Grove to pick up medical personal, and then went on to arrive at Edmonton at 9 a.m. November 22. In Kamloops, Jasper, and Edmonton the media was forbidden to discuss with, talk to, or take pictures of the soldiers, nurses, doctors, and passengers of both trains. The uninjured soldiers were happy to help carry their injured friends into the hospital, but everyone was quiet when the unmoving bundles were brought in.

7

An injured man being removed from the hospital train in Edmonton22 November 1950

Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

Credits:

Credits:Korean Veteran Association Unit 21

8

Army flies soldiers home to Toronto, Montreal and HalifaxDecember 1950

Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

Credits:

Credits:City of Edmonton Archives EA 600 6297

Photographer Eric Bland / Edmonton Bulletin

9

The Preliminary HearingTwenty-two year old John Alfred Atherton, dispatcher for Red Pass, was charged with manslaughter for the death of Henry Proskunik, the fireman on the troop train, in early January 1951.

Atherton was released on bail January 23, 1951. The two men who bailed him out were Alex Moffat - proprietor of Northern Hardware and Furniture Company Ltd and William Reynolds, a C.N.R. employee. Atherton immediately went home to Saskatchewan to wait for the preliminary hearing.

John G. Diefenbaker, a well known criminal lawyer, was his defender. This case was the most sensational case in his career. Diefenbaker only became his defender because his dying wife Edna told him to be. She never got to see the result; she died before the trial. He had to pay $1,500 dollars and go through an examination to become a member of the B.C. bar to take on the case. In the preliminary hearing, Diefenbaker cross-examined many people and questioned several C.N.R. employees on the stand. He revealed the fact that if there is a lot of snow or if a bird puts a dead fish on the wire (it has happened before), part of the message being transmitted will blank out. The hearing went well, but was not good enough. Diefenbaker's motion for Atherton's dismissal was dismissed and Atherton was committed to stand trial on charge for manslaughter.

10

The TrialAtherton's trial opened in Prince George on May 10, 1951. Justice A.D. McFarlane presided and a 12 member jury was selected to hear the case. The Crown prosecutor was Eric Pepler, Deputy Attorney General for British Columbia. He was a decorated World War I Officer, who was wounded in the war.

On the first day of the trial, Diefenbaker insisted on talking about the wooden cars with steel framing. The cars should have been steel. Diefenbaker said that in all his time he had only ever seen soldiers transported in wooden cars. Diefenbaker said, or rather asked, "I suppose the reason you put these soldiers in wooden cars with steel cars on either end was so that no matter what they might subsequently find in Korea, they'd always be able to say, 'Well we had worse than that in Canada ?"

The judge found this improper and argued that this was a statement rather than a question. The judge said, "Well, I'm very doubtful, but ?" Then Colonel Pepler interrupted, "I want to make it clear that in this case we are not concerned about the death of a few privates going to Korea."

What Pepler meant was that the charge did not include the death of the soldiers, but rather the death of a C.N.R. crewman. Diefenbaker used Pepler's error to his great advantage. He said, "Oh, you're not concerned about the killing of a few privates? Oh, Colonel!"

There were two old soldiers from the First World War on the jury and one said loudly to the other, "Do you hear what that blankety-blank said?"

From then on things went Diefenbaker's way. For the next two days, Diefenbaker often took the attention away from Atherton's charge by accusing the C.N.R. saying that the mistake was not human, and the railway company needed to take more safety precautions. The jury deliberated for 40 minutes before returning their verdict.

Atherton was acquitted.

11

TelegraphsKamloops - Transmitted by dispatcher Eugene Tisdale

PSGR. EXTRA 3538 WEST MEET NO 2 ENG 6004 AT CEDARSIDE AND NO 4 ENG 6057 GOSNELL

Blue River - Transmitted by operator Frank Parson

PSGR. EXTRA 3538 WEST MEET NO 2 ENG 6004 AT CEDARSIDE AND NO 4 ENG 6057 AT GOSNELL

Red Pass - Transmitted by telegrapher Alfred John Atherton

PSGR. EXTRA 3538 WEST MEET NO 2 ENG 6004 AND NO 4 ENG 6057 GOSNELL