13

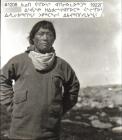

Igjugaarjuk, Inuk from Yathkyed Lake1922

Hikuliqjuaq, Yathkyed Lake, Nunavut, Canada

Credits:

Credits:Rasmussen, Knud

Photo #1208. The Fifth Thule Expedition

National Museum of Denmark

14

RCMP Annual Report year ended September 30, 1920ROYAL CANADIAN MOUNTED POLICE COMMISSIONER'S REPORT

11 GEORGE V, A. 1921

SESSIONAL PAPER No. 28

ALLEGED MURDERS NEAR BAKER LAKE

"In the winter of 1919-20, Sergeant W.O. Douglas was in charge of the detachment at Fullerton. This detachment, over 400 miles farther north than Churchill, and 100 miles up the coast from Chesterfield Inlet, at this period was the centre of very active patrolling; from September, 1916, to January, 1919, the distance covered by patrols based on it was nearly 16,000 miles.

On December 19, 1919, Sergeaant Douglas, with Constable Eyre and two natives left Fullerton for Chesterfield Inlet, arriving on December 22, after being delayed for a day by a blizzard. At the Hudson's Bay Company's post a letter was waiting for him from the manager of the Hudson's Bay Company's post at Baker Lake, 150 miles inland up Chesterfield Inlet, informing him that two of this hunters had been murdered by another native, that the murderer was at large, and that the native population of the region was badly frightened. Sergeant Douglas at once decided to go up the Inlet to Baker Lake. The necessary arrangements took time as it was necessary to get additional dog-feed, etc. From Fullerton; and on January 1, 1920, Sergeant Douglas, after sending Constable Eyre back to Fullerton, set out for Baker Lake; he had with him two natives and two dog t4eams. He arrived at Baker Lake on January 8.

The information obtainable was meagre. An Eskimo of the Paddlemiut tribe named ou-wang-wak, living about 150 miles south, was reported to have shot dead two brothers, also of the same tribe, named Ang-alook-you-ak and Ale-cummmick, and had appropriated the wife of the former. The other Eskimo were so afraid of Ou-ang-wak that they were keeping away from the Baker Lake post. Sergeant Douglas resolved to patrol to the scen of the murder, to investigate, and if necessary to arrest the accused. At once difficulties arose which delayed him for nearly three weeks, for the natives were afraid to accompany him. He reports:-

"I experienced great difficulty in getting anyone to make the trip. At last I managed to get a native who assured me he knew the country, but refused to pull out with less than three sleds and four or five men. He said that he had heard that this native had said that he would never be taken alive by the Police. This he gave as a reason for wanting such a large outfit.

After much trouble, Sergeant Douglas got together a party of four Eskimo men and the wife of one of them, together with three dog trains, and left Baker Lake on January 27. An illustration of the difficulties of travel in these regions is afforded by the party's pre-occupation with dog-feed; none of this was carried on the journey and the animals on which their transport depended lived for the first four or five days on deer (caribou) which were shot as the party went along, and for the rest of the time on an insufficient amount of "summer cache meat' which Sergeant Douglas managed to buy.

On February 5, they arrived at a native camp of two igloos, and found two lads of a tribe whose name is variously spelled as Shav-voe-toe and Shag-wak-toe. Sergeant Douglas's natives were so afraid of Ou-ang-wak-they thought he might be there-that he had difficulty in inducing them to drive up to the igloos and see who the inhabitants were. 'It caused much laughter amongst themselves when they found that one of the men was a guide's own brother-in-law.' The news was that the object of the search was encamped about two days farther on, and he had been warned by some white men that the Police would be after him and would kill him (due to capital punishment) and that he was in a state of extreme nervousness. 'When last seen by these lads, he was sitting in his igloo with his hand over his face, and every few minutes getting up and getting out to see if there were any strange sleds about.'

All this increased the dread of Sergeant Douglas's natives, and they resolved to go home. He found that there was a native camp midway between the place where they were and Ou-ang-wak's camp, and he, in the end, persuaded his escort to proceed to this half-way house. The arrived there on the afternoon of February 7.

'On our arrival at this camp we were met some distance from the igloos by a young lad who wished to find out all about us and report to the chief. After some delay he returned and told us that Edjogajuch, the chief of the tribe, wished to see us in his igloo. Negvic, the guide, Native Joe and myself returned with this man, the other two members of the party staying with sleds. After entering the igloo, I shook hands all around, took off my koolotang (caribou coat for outside), sat up on the bench beside the chief and told him that we were hungry and would like to eat with him. He produced a frozen deer and several small butcher knives. We all sat around and ate. This put things on a better footing and all the natives started to talk, and our other two men came in. After we finished eating. I produced tobacco and matches and when everybody had got their pipes going, with Native Joe as an interpreter. I told them what I had come for.

'Edjogajuch replied saying he was sorry that I had come, and telling me that Ou-wang-wak was living one day's travel from his camp. He also warned me not to go there as he had just left this camp and was afraid that if a white man went there and tried to bring away Ou-ang-wak there would be shooting.

'This put the finishing touch to my natives and they refused point blandk to go ahead another step.'

Negotiations ensued.

'I had an igloo built and sent for Edjogajuch. I then told him through the interpreter that I had heard that one of his tribe, Ou-ang-wak had killed two men. He replied that this was so. I further told him that this was contrary to white man's law, and that I was down here to see that Ou-ang-wak and that I was not leaving without doing so. I then suggested that in the morning he take me to the camp across the lake. This he refused to do, as he said that he also might get shot.

'I tried again to get my natives to go with me to this camp, but without success. I sent again for Edjogajuch and told him that I looked upon him as a chief in this district, and it was up to him to either to take me to this camp or go there himself and bring this native Ou-ang-wak to me. He said that he would not go with me but would go alone and try and get him. I told him that I would wait here at this camp for three days and if at the end of that time he was not back, or had no word fo him, I should come myself to look for Ou-ang-wak. He was much afraid as he undoubtedly believed that as soon as I saw Ou-ang-wak I should shoot him. I gve him my word that no harm would come Ou-ang-wak or any of the natives if they did what was right and showed no strife.

Accordingly, on February 8, Edjogajuch left his camp, and late in the afternoon of February 9 he returned with Ou-an-wak and the woman." (pages 11-12).

On their arrival at the camp Sergeant Douglas arrested Ou-ang-wak and, 'I then told him that he would have to come with me to the white man's land as the Big Chief there wanted to see him. He asked me what they were going to do with him and would they kill him. I told him that I had no idea, but I assured him that if he acted square with me he would be looked after well and taken outside to the Big White Chief...'

Sergeant Douglas took Ou-ang-wak and the woman to Baker Lake, Chesterfield Inlet, and Churchill Manitoba. He then took Ou-ang-wak to Fort Nelson, The Pas, and then to Dauphin, Manitoba.