14

The trail from Cobiquid (Truro) to Tatamagouche, rough in places, followed the Chigonois River18th Century, Circa 1710

Earl Town, Colchester County, Nova Scotia

Credits:

Credits:Charlotte Moody

15

British soldier re-enactors from the Acadian Deportation period18th Century, Circa 1755

Remsheg, one of 19 ways to spell the Mi'kmaq name for the village in Nova Scotia now Wallace

Credits:

Credits:David Dewar

16

Lt. Governor of Nova Scotia, Charles Lawrence; The Deploration took place under his command8th Century, Circa 1753

Nova Scotia

Credits:

Credits:Nova Scotia Archives

17

Re-enactment soldiers of the Deportation period18th Century, Circa 1755

Remsheg, one of 19 ways to spell the Mi'kmaq name for the village in Nova Scotia now Wallace

Credits:

Credits:David Dewar

18

Captain Willard stopped a few miles from Cobiquid to read his sealed orders14 August 1755

Earltown, Colchester County, Nova Scotia

Credits:

Credits:Charlotte Moody

20

Acadian expulsion orders being carried out in Remsheg15 August 1755

North Wallace Road, Wallace Bay Cumberland County, Nova Scotia

Credits:

Credits:Barbara Clark

21

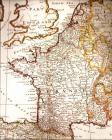

Map of 17th Century France showing the area in Normandy from which many of the French came to Acadia18th Century

France

Credits:

Credits:Wallace and Area Museum

22

Dykes and Aboiteaus18th Century, Circa 1720

Nova Scotia

Dykes and aboiteaus were used by the Acadian settlers to protect and improve the fertile marshland.

First, the Acadians would build a dyke to surround a desired marsh area, to protect it from tidal flooding. These dykes were all constructed by hand using simple hand tools, sleds, and sometimes oxen. Some dykes could be several kilometres in length. Normally they would be built about 3 metres above the high water mark. The average daily tide rise in this area is 1.5 to 2.5 metres, but can be much higher in the spring and fall. Places had to be found to excavate fill to build the dyke. In today's construction these areas are called "borrow pits". Aerial photos show many pitts along dyke construction, telling us the material was always near to the construction site.

Next, the farmers would install an aboiteau in the low areas along the dyke. An aboiteau is a simple wooden valve using a wooden flap to control water flow. It was installed to allow rain water or snow melt water to drain from the land which helped leach out the salt from marsh soil, making it very productive farm soil. The leaching process took three to four years.

When a breach of a dyke happens, through storms or floods, it was devastating for farmers to lose large sections of their crop land.

Credits:David Dewar

23

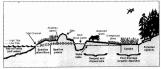

Diagram of a working dyke18th Century,

North Wallace Road, Wallace Bay Cumberland County, Nova Scotia

Credits:

Credits:Nova Scotia, Ducks Unlimited Amherst

24

Rich marshland at Remsheg Bay, first seen by Acadian farmers in about 171021st Century, Circa August 2010

North Wallace Road, Wallace Bay Cumberland County, Nova Scotia

Credits:

Credits:David Dewar

25

Model of working aboiteau; in the foreground are drainage ditches sloping to the aboiteau at the top

26

Model of a working aboiteau18th Century design. Circa 1720

Tuttle Creek, Wallace Bridge, Cumberland County, Nova Scotia.

Credits:

Credits:Jim Reeves, model maker

Zella Perry, Photographer

27

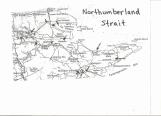

Map of North Cumberland County area with evidence of Acadian habitationModern map of 18th Century Acadian life

Northumberland Strait, Cumberland County, Nova Scotia.

Credits:

Credits:David Dewar