1

Medicine & MidwiferyMedicine in Yale

From Dr. Fifer to Dr. Hayashi, from Jessie MacQuarrie to many others, there have been doctors and midwives in Yale since the Gold Rush days.

The tale of Dr. Fifer is a most interesting and tragic one, but there are also more stories than his to be told.

With available doctors at a premium and many locations being rural, woman often assisted one another during child birth. Some of these women built reputations as midwives in these areas despite the lack of any formal training (if there was any for midwifery). We will be telling about one of these women.

Please take your time and enjoy this peek into the past.

2

The signature of Dr. Max Fifer The correspondence was directed to Colonel Moody25 June 1860

Yale B.C.

3

Dr. Max William FiferMurdered by Malice and Misunderstanding

(Warning: this story contains text that describes specific medical terms and procedures; and may not be suitable for young readers. Parental guidance is recommended)

Dr. Max William Fifer was a well respected medical man in Yale until his murder in 1861. His arrival in Yale corresponds with many past residents who found their way to the bustling town in 1858. His right hand man was Ah Chung, who came with him from San Fransisco. 1

Earlier in his career, Fifer served in the US/Mexican War where he was a Hospital Steward. He and many other veterans of the war dabbled in mining following their disbandment. Fifer had made a considerable fortune that helped fund his decision to become a doctor.

He set up practice in San Francisco after obtaining his education and was active in the California State Medical Association. When a friend informed him that British North America was on the verge of a gold rush Fifer decided to head to the colony.

Fifer established a medical practice in the town of Yale, the hub of activity for the Fraser River Gold Rush. While in Yale Fifer became involved in the politics of a town that was struggling to adapt to its new found importance. He even had the ignoble distinction of being punched in the face by Ned McGowan in 1859.

Dr. Fifer brought two objects with him from the USA, the skull of his office skeleton, and an old apothecary's bowl from his time in the Mexican War. Both objects have colourful stories attached to them from after Fifer's death.

Dr. Fifer cared deeply for his patients. He treated everyone to the best of his ability and pulled knowledge for their treatments from a large array of sources. Some of the cases met with resounding success and others with failure. At times he found himself pitted against the medical professionals from Britain who saw his American training as substandard and yet some kind of threat. One of these doctors even became malicious toward him.

It was while treating a patient that resulted in a combination of success and failure that Fifer met his untimely end.

Robert Wall was a prospector with a serious medical condition. He had a venereal disease that caused swelling and pain. Raging lust forced him to continually abuse himself or find relief with prositutes, thus he contracted the disease; which complicated the symptoms from his lust. The swelling grew so bad that he had to waddle slowly when he walked, and the problem was visible to others.

Wall was broke but desperate, and promised to pay Fifer when he could, if he could only help him put an end to his suffering.

Fifer lanced the boils, releasing gushes of yellow pus, and giving great relief to the patient.

In his famous mortar the doctor ground up a concoction of aconite & wolfsbane, and worked in cerate (beeswax).

He told Wall to use this salve every day, and it worked quite well. After a time the swelling went down, but it also deadened Wall's feeling in that area and left him impotent.

When he had used up the ointment he went to another doctor, as he still owed money to Dr. Fifer. Wall complained to Dr. Crane about his impotence, and the physician saw an opportunity to discredit Fifer. With malice he blamed Fifer for Wall's problems and told him that he was beyond medical help, that Fifer had irreversibly damaged him.

This information drove Wall over the edge, and he swore to kill the doctor. For two years he nursed his grudge and made his plans, becoming a vagabond and loitering about in various towns around the lower mainland of B.C.

In 1861, the day after a large 4th of July celebration by Americans in Yale, four men in a canoe pulled up to the Yale beach. While the others hung around town for a while, one man made his way to Dr. Fifer's office and inquired after the doctor. Ah Chung directed him to the back room, and the man walked in, saying, "Dr. Fifer, look at this."

He had a folded newspaper in his hand. The physician took the paper, looking down at it, and the man produced a small pistol and fired it point-blank at Fifer's chest.

The doctor died within a minute or so, sliding down the wall, a surprised look on his face.

The man, who was Robert Wall, gazed at his victim's body for a few moments, then calmly turned and walked back to his canoe, where his friends waited. They left as quietly as they had come, heading downriver to Hope.

"With all speed, three canoes were manned and the fugitive was followed." 2 Four days later Wall was arrested by a posse near Fort Langley.

Wall was tried in Yale under Judge Begbie, and hanged, appropriately thought many, over the grave of his victim.

Nearly the entire populace of Yale were present at Dr. Fifer's funeral. In his tragic murder they had lost an upstanding member of the town and a valued medical professional. They grieved for the loss of a life with the potential to become a prominent part of the history of B.C., that was cut too short.

Though Fifer tried to do his best, he invariably had to deal with heartbreaking losses.

"Another child patient was Sara, the youngest daughter of Ovid Allard, the clerk of the Hudson's Bay post. The little girl had been allowed on an outing across the river with her older sister Lucie (sic). While looking for wild strawberries, Sara had become lost and had fallen asleep under a scrub maple. She was awakened by the crackling of a miner's campfire. Cowering behind the bush, Sara observed the swarthy miner sitting by the glowing embers and taking from his shoulder bag a large potato. With his knife he cut it in half, scooping out a hole. Into the hollow space he placed a walnut-sized ball of a grayish, putty-like substance. He wired the two halves back together and placed the potato on the red-hot bed of coals. With two sticks he turned it often to bake it evenly. It was almost charred on the outside when he gently eased it off the fire and allowed it to cool. He removed the wire and opened the two halves. To Sara's amazement he took out a shiny piece of yellow gold from the centre and placed it into his poke. He kicked the potato to the side, and, whistling a tune, the miner went off toward Hill's Bar.

Sara came out of her hiding place. She had had nothing to eat since morning. The fragrance was mouth-watering and reminded her of the potato roasts at Fort Langley. Hungry as she was, the devoured the potato.

Later, at home, she collapsed. Her parents called Dr. Fifer, who was their neighbour across the back lane. The doctor was confused by the girl's incoherent story that she had eaten some baked potato. He suspected that she had fallen victim to an unknown miasma and administered tincture of opium, called laudanum, and a mercury compound, calomel. He decided to bleed her; though he would have preferred the gentle leeches, none were available, and he had to resort to the painful method of lancing. The treatment seemed to settle her and her cramps and diarrhea subsided. The doctor stayed at Sara's bedside continuously and watched as her face became puffy and her breath sweetish as a result of renal failure, and then he realized that her young life had slipped through his fingers. The mother was beside herself with grief over the loss of her youngest child and refused the laudanum Dr. Fifer offered for her distress.

On the following day Dr. Fifer was in his office. He was totally unprepared when Mrs. Allard stormed in and, in front of the patients, accused him of malpractice and blamed him for Sara's death. Then she attacked him, pummeling him violently, knocking the gold-framed spectacles off his nose and rendering him defenseless in his short-sightedness. He was not a tall man and disliked violence, and against a woman who was temporarily out of reason, he would not defend himself.

After she left, Dr. Fifer became concerned about the bad publicity that this incident might cause. To his chagrin the British Colonist printed a full account of the embarrassing assault in the following week's issue - by which time the mother and the doctor had become reconciled." 3

It seems fairly obvious that poor Sara likely died of mercury poisoning, as it was mercury that was used by the miners to separate the fine gold from the black sand. A freak accident that was not really anyone's fault. A tragedy at its most ironic, and a very hard event for both the Allards' and the doctor to accept.

The tale of the skull is a good one. Many years after the doctor's death, Ah Chung was well established in San Fransisco's Chinatown with his herbalist's shop. He was visited one day by a Northwest Mounted Police officer from Canada. He was told that, after Fifer's old house had burned down, the skull of a woman was found in the ashes, and the police suspected that the two men had had a woman living with them in secret, with a foul ending.

Ah Chung cleared things up right away by explaining that the skull was the only part of his medical skeleton Fifer had room bring with him when he was packing to move to B.C. He also stated that the doctor had been interested in phrenology, the science of studying bumps on the skull for their hints about aspects of the human brain such as morality, intellect, and sensuality.

The tale of his apothecary vessel is a nice one. After the US/Mexico War ended, he took a souvenir, a small medicine bowl, used for grinding medicines. Dr. Fifer had a fondness for using his morter and pestle, and brought it to Yale with him despite the fact that they were rarely used anymore, as most druggists now dispensed powders.

After Fifer's murder, Ah Chung took the bowl with him to San Fransisco, intending to give it to the physician's daughter as a keepsake, one of her father's favourite objects. Sadly, he could not locate her, though he looked a long time.

Thirty years after leaving Yale, Ah Chung decided to return the vessel to rest with Dr. Fifer's remains. To his chagrin, the CPR track ran right over the spot where his mentor was buried. He resolved to take it home with him again, but fortunately met Thomas Fraser Yorke at the Sumas border crossing and told him his tale. He found that Yorke, the first white child born on the BC mainland, had been delivered by Fifer; and the bowl, along with this story, after some time with the Yorke family, found it's final resting place in the Vancouver City Museum. This very brief description does not do justice to the full tale, and Dr. Asche's version is well worth reading. 4

There are many other interesting stories about Max Fifer, that will be published soon in a book by Dr. Gerd Asche, who has kindly given us permission to use this information prior to publishing.

1- This information was obtained through the research of Dr. Gerd Asche, a former physician of Hope, B.C. who has made it his quest to search out the life and times of a man that he refers to as his predecessor, Dr. Max Fifer.

2- Dr. Gerd Asche, "No Cock for ∆sculapius", BC Medical Journal, Vol. 38, #9, Sept. 1996; pp 511-514

3- "Government Says No to Medicare (1858)" by Dr. Gerd A. Asche, MD; 'Back Page', p.365, BC Medical Journal - Vol. 37, # 5, May 1995

4- Dr. Gerd Asche, "The Vessel", unpublished as yet.

4

Jessie and Daniel McQuarries' graves. They passed away within days of one another.November, 1911

Yale B.C.

5

The Midwife and the ShoemakerJessie & Daniel MacQuarrie

1853 - 1911; 1839 - 1911

She was a Midwife in Yale,

He a Maker of Boots and Shoes

Jessie Ann Milroy Kellie MacQuarrie bears a stature to equal the largess of her name. Not only was she responsible for delivering many babies during the later 1800's in Yale, but she also had at least ten of her own, one even delivered by her husband.

Daniel Donald MacQuarrie was a boot and shoe maker; his shop was called "Custom Shoes", and was located on Front Street. The MacQuarries owned a farm at Gordon Creek, about one mile west of Yale.

The MacQuarrie family history is intertwined throughout the story of Yale. Their shop is documented in the Yale Business Directories of 1877 through 1885. There is a D. MacQuarrie listed as the Yale Post Master for 1872, perhaps attesting to their arrival in Yale. Daniel has also been recorded as being the trustee for the Yale fire department between 1882-1883.

He was also involved with the Yale Public School, mentioned in The Daily Colonist - Dec. 28, 1886. Before an audience of the local townsfolk, during the year-end examination; "Messrs. Fraser, Teague and MacQuarrie favoured the assemblage with appropriate remarks."

Jessie's name shows up often as the accoucher or medical person present, on many of the birth records pertaining to Yale between the years of 1885-1901. She assisted the births of the Bessi child in 1885, Browns in 1886 and 1891, Corrigan in 1893, Hantz in 1898 in Spuzzum, and in 1901 for the Davenport's baby at the Hope Station.

Daniel and Jessie's children were Margaret Thomas (1876), Alexander Kellie (1878), Elizabeth Turner (1879), Jessie Kerr (1880), Agnes Catherine Joanna (1883), Marion Isabella (1884), Donald Gladstone (1886), William Yale (1888), James Kellie (1890), and Roy Douglas (1893). The first eight children were born in Yale, and the last two, James and Roy were born in New Westminster.

William Yale MacQuarrie was delivered by his father Daniel on April 20, 1888. It is easy to imagine that by this time Jessie would have had no problem guiding her husband through the procedure as she gave birth to their son.

According to the remembrances of Walter Chrane, a local grandson of William Teague, his mother Gladys was a schoolmate of the MacQuarrie children.

He states that one day Alexander MacQuarrie was playing on the railroad tracks; he was attempting to see how many times he could run across before the train got to him. The train hit him in front of a large number of horrified spectators. He was badly hurt but not killed, and apparently had brain damage, as Mr. Chrane stated that Alexander was never right in the head after his recovery. It appears that he died years later at Colquitz in 1934.

At some point Daniel MacQuarrie must have moved away from his family, perhaps due to illness or a business venture, because the 1901 Census records Jessie as the head of the family at that time, though Daniel's death record and headstone place his death in 1911. He died in New Westminster, so it must be assumed that he was residing there. This may explain why the last two children were born in New Westminster.

Daniel was born in Glasgow, Scotland April 26, 1839; and Jessie was born in Southampton, Ontario on May 1, 1853.

Jessie and Daniel died only one month apart from each other in 1911; Daniel on October 8th and Jessie passed away in Yale on November 14th. Jessie died of Apoplexy. 1 She was buried beside Daniel, who was buried in the Yale Cemetery on Oct.13, 1911.

1- Apoplexy - the sudden loss of consciousness and motive power, resulting from cerebral rupture. Motive - loss of movement)

6

Yale's Chinatown DoctorsYale experienced a resurgence of population with the establishment of the Canadian Pacific Railway. Andrew Onderdonk, who had the contract to build the railway through the Fraser Canyon, logically decided to base operations out of Yale.

The building of a railway through the Fraser Canyon was filled with perils, some anticipated and many more unexpected. There are tales of horrific disasters and men who died while risking their lives. A large percentage of these men were of Chinese origin.

Dr. Donald McLean was appointed as the doctor for the CPR's Chinese construction workers in 1881. He left in 1883 for Chilliwack.

Dr. Hanington was brought in by Andrew Onderdonk as the Doctor for the railway hospital, serving from 1882 until 1885.

The Chinese people also had their own brand of medicine and were able to obtain it from Dr. Po On or Dr. Yuen Sing Tong. Both Chinese doctors had left Yale by the time Onderdonk completed the railway in 1885.

The presence of a doctor within Yale's Chinatown existed long before the building of the railway ever became a reality. As early as 1860, during the Fraser River Gold Rush, a visitor to the area reported that "one building particularly arrested our attention - a large wooden edifice built by the Chinese for a hospital, showing that these people, upon whom we are wont to look upon with contempt, shame us in this matter."1

1 British Columbian, Sept. 26, 1861

7

Depiction of a portion of China town in Yale highlighting the Kwong Lee Store and the hospital.1997

Front Street, Yale

8

Dr. Donald McLeanDoctor for Chinatown

Dr. Donald McLean was appointed as the doctor for the CPR's Chinese construction workers in 1881. McLean got his degree in medicine at the University of Edinburgh. He was born in Scotland around 1835, and moved to the United States to sit for a term under Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes, a professor at Harvard University. From there he moved up to Yale, where he had received his posting.

While residing in Yale, Dr. McLean met Maggie McPhee, the daughter of Neil McPhee, a provisions merchant. Maggie and Dr. McLean were married on October 8, 1881 by the Justice of the Peace and registrar for the area, Walter Dewdney.

Dr. McLean became a well known figure in Yale, despite the competition of Dr. Frickelton, an established doctor in Yale. A report of the great fire that tore through Yale in 1880 was printed in the Inland Sentinel. It recalls Dr. McLean's efforts, as well as the efforts of others who tried to counteract the impact of the fire, while criticizing the individuals that failed to lend a hand. The article reads "Mr. McCormack was not in Railway employ and Dr. Mc.Lean was called upon and was promptly on hand to render what assistance could be given in so critical a case, as the sufferer was badly burned; we learn he has since died." 1

Donald and Margaret moved to Chilliwack in 1883, then on to New Westminster and Elgin. Dr. McLean died in June of 1892, and is remembered in Yale for his willingness to help others whenever there was someone in need.

1- "The Fire-Fiend at Yale." The Inland Sentinel, July 29, 1880.

10

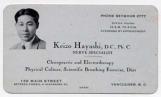

Dr. Keizo Hayashi1902 - 1994

"Chiropractor of the Fraser Canyon, and Yale's Greatest Benefactor"

Dr. Keizo Hayashi loved Historic Yale and the Fraser Canyon, and became its best benefactor in modern times. He may have been repaying the confidence and kindness shown to him by Yale people during World War II.

Dr. Hayashi was a respected chiropractor in the Fraser Canyon area for more than 50 years. Many patients "traveled for miles to receive consultation and treatment" 1

Keizo Hayashi was born on April 25, 1902 at Cowan's Point, Bowen Island, B.C. Not much is known of his early life there.

He received his chiropractic training in Portland, Oregon. His first practice was likely in Sirdar, a tiny town in B.C.'s East Kootenay region, and he may have worked there until 1931.He is remembered by a gentleman who lived there when he was about 6 or 7 in that year.

In 1931 Dr. Hayashi received his licence to practice in Vancouver and opened an office at Hastings and Carroll Street. After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour during the Second World War all citizens of Japanese descent were sent to internment camps. Hayashi was sent to the camp in Princeton.

Before the war he had become acquainted with Mr. Haskell, a lawyer, his wife Gwen and her sister Helen Moore. Haskell vouched for Hayashi and he was released into their care.

"During those days if there was a recognized sponsor or sponsors and the location of residence was a hundred miles or more from the Port of Vancouver a release could be arranged." 2

The Haskells bought a small farm at Gordon Creek one mile south of Yale in 1942. "It was there in Gordon Creek where the Haskells and Miss Moore and Dr. Hayashi constructed a very comfortable home." 3

Dr. Hayashi opened his Hope office in 1951 and continued his practice into the 1980's. Mrs. Haskell and Miss Moore assisted with the office duties. Even after his retirement the doctor continued to help people with his treatments and natural processes.

One of Dr. Hayashi's favourite hobbies was jade collecting. He would hike all over the Fraser Canyon area as far up as Lytton. He also made original jewelry and had a completely equipped rock shop at Gordon Creek.

After Mr. Haskell passed away, Mrs. Haskell, Miss Moore and Dr. Hayashi remained inseparable. They all continued to reside at Gordon Creek and took very good care of one another. Gwendoline Haskell passed away at age 87 in the Chilliwack Hospital in 1978. Her sister Helen Moore fell ill, and was also hospitalized, first in Hope, and then in Chilliwack for several years. Dr. Hayashi drove to Chilliwack every day to care for her, and when he could no longer drive he took the bus. He fed and looked after Miss Moore every day until she passed on.

"The devotion shown by Dr. Hayashi during the illnesses experienced by the sisters was always above and beyond compare. Keizo moved to a care home in Chilliwack B.C. but on every opportunity returned to the homestead and to visit with friends in Hope and Yale B.C." 4

Dr. Hayashi was held in great respect by friends and patients. His service to the community extended above and beyond the call of duty and friendship, and he particularly showed his appreciation to the family who had kept him from the internment camps. He died at the fine old age of 92 in Chilliwack on April 10, 1994.

Upon his death Dr. Hayashi left a full third of his estate to the Yale & District Historical Society, to use as they thought best. The YDHS set aside an endowment fund out of this for the upkeep of the Yale Pioneer Cemetery.

1- Article written by Mary McQueen for the Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College in 1997. Summary of write up done by Darla Dickinson, YDHS.

2- Ibid

3- Ibid

4- Article written by Mary McQueen for the Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College in 1997. Works. Yale & District Historical Society Archives

13

Medicine & MidwiferyThere were many more doctors in Yale throughout its history than have been recorded here.

Yale had an accident hospital that saw much use during the building of the CPR, as well the Chinese community had their own hospital.